7,000-year-old seals in Beit She’an used to keep elections honest

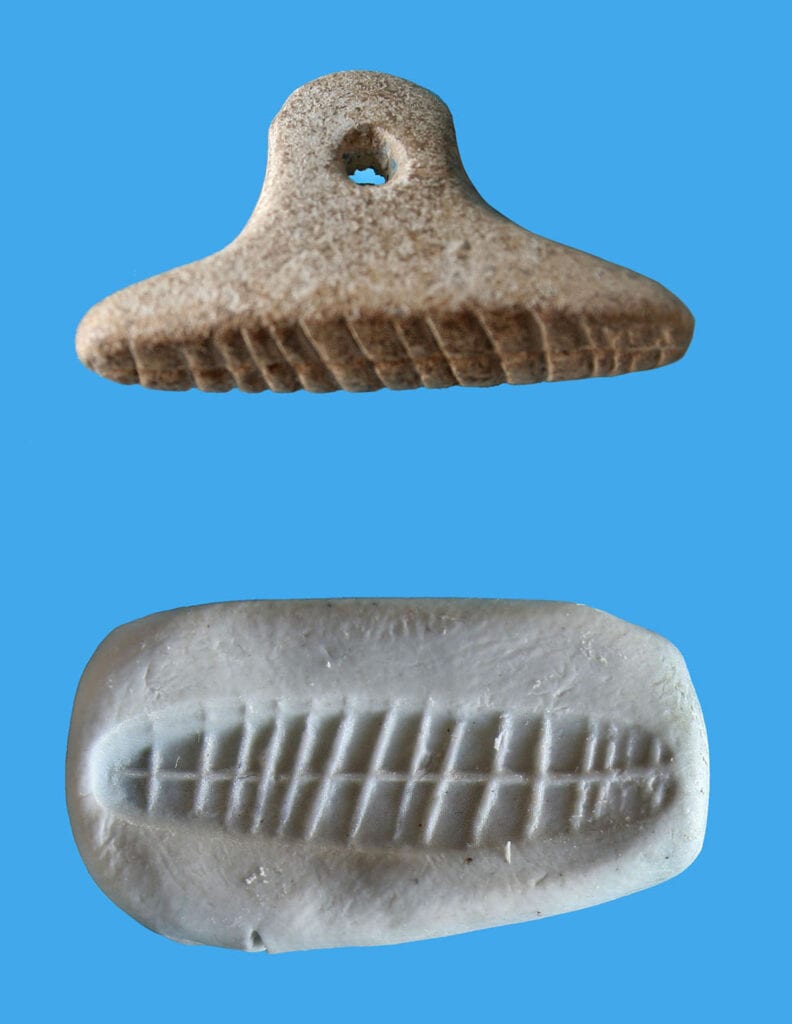

Tel Tsaf seal with modern impression_Credit Vladimir Nichen

When Israel (too-frequently) holds elections, the tens of thousands of plastic boxes containing the millions of ballots deposited in them by voters are locked with a seal to ensure that there was no tampering. This is taken for granted.

Now, a team of archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI) has made a rare discovery when they unearthed a small clay seal impression dating back some 7,000 years. Sealings – also known as bulla – are made of a small piece of clay were used in historical times to seal and sign letters and to prevent others from reading their contents.

The sealing with two different geometric stamps imprinted on it was discovered in Tel Tsaf, a prehistoric village located in Israel’s Beit She’an Valley in northern Israel. This discovery is especially significant because it is the first evidence of the use of seals to mark shipments or to close silos or barns. When a barn door was opened, its seal impression would break – a telltale sign that someone had been there and that the contents inside had been touched or taken.

Seal impression on clay bulla. Photo by Tal Rogovski

The discovery was made as part of a dig that took place between 2004 and 2007 and was led by HUJI’s Prof. Yosef Garfinkel along with two of his students, Prof. David Ben Shlomo and Dr. Michael Freikman, both of whom are now researchers at Ariel University in Samaria.

It took so long to make the discovery because during the digging season, the archaeological team end up with tons of material. They first study the larger pieces/shards/findings and then sift through the rubble looking for tiny fragments that are less that one centimeter wide; this was the sealings that they found.

In fact, 150 clay sealings were originally found there, with one being particularly rare and of distinct, historic importance. The object has just been published in the journal Levant under the title “A stamped sealing from Middle Chalcolithic Tel Tsaf: implications for the rise of administrative practices in the Levant.”

Prof. Yosef Garfinkel (Courtesy)

“Even today, similar types of sealing are used to prevent tampering and theft,” explained Garfinkel. “It turns out that this was already in use 7,000 years ago by land owners and local administrators to protect their property.”

The tiny fragment was found in excellent condition due to the dry climate of the Beit She’an valley. The sealing is marked by symmetrical lines. While many sealings found in First Temple Jerusalem (about 2,600 years ago) include a personal name and sometimes biblical figures, the sealing from Tel Tsaf is from a prehistoric era, when writing was not yet in use. Those seals were decorated with geometric shapes instead of letters. The fact that there are two different stamps on the seal impression may indicate a form of commercial activity where the two different people were involved in the transaction.

The found fragment underwent extensive analysis before researchers could determine that it was indeed a seal impression. According to Garfinkel, this is the earliest evidence that seals were used in Israel about 7,000 years ago to sign deliveries and keep store rooms closed. While seals have been found in that region dating back to 8,500 years ago, seal impressions from that time have not been found.

Based on a careful scientific analysis of the sealing’s clay, the researchers found it wasn’t locally made but came from a location at least ten kilometers away. Other archaeological finds at the site reveal evidence that the Tel Tsaf residents were in contact with populations far beyond ancient Israel.

“At this very site we have evidence of contact with peoples from Mesopotamia, Turkey, Egypt and Caucasia,” Garfinkel added. “There is no prehistoric site anywhere in the Middle East that reveals evidence of such long-distance trade in exotic items as what we found at this particular site,” the Jerusalem archaeologist explained.

Silos at Tel Tsaf. Credit Boaz Garfinkel

Tel Tsaf excavations. Rectangular House and rounded silos. Photo courtesy

The site also yielded clues that the area was home to people of considerable wealth who built up large stores of ingredients and materials, indicating considerable social development. This evidence points to Tel Tsaf as having been a key position in the region that served both local communities and people passing through.

“We hope that continued excavations at Tel Tsaf and other places from the same time period will yield additional evidence to help us understand the impact of a regional authority in the southern Levant,” concluded Garfinkel.

Israel in the News