Although Jewish Holocaust survivors – who are today on average 85-years old – are generally considered an amazingly resilient group despite the terrors that they endured. Those that suffer from post-trauma have been found to adopt harmful health behaviors like smoking, drinking alcohol and avoiding physical exercise. Unfortunately, these survivors also tend to “hand down” such behaviors to their adult children, who are now middle-aged or even older.

There are about 152,000 Israeli Holocaust survivors alive today – and the number is due to drop to an estimated 140,000 in 2020, 92,600 in 2025 and 26,000 a decade later. On average, one Holocaust survivor dies in Israel every 45 minutes – or more than 1,000 per month.

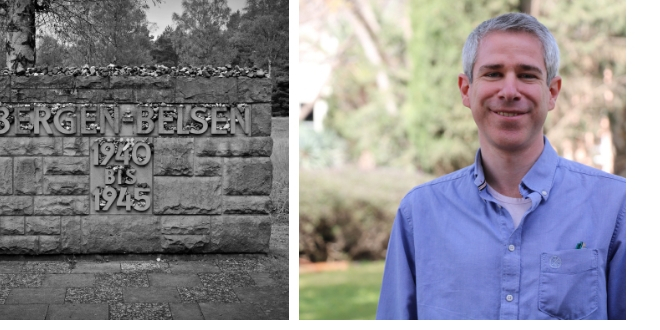

A new study at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan near Tel Aviv on intergenerational transmission of trauma has found evidence that Holocaust survivors suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and their adult children exhibit more unhealthful behavior patterns and age less successfully compared to survivors with no signs of PTSD or parents who did not experience the Holocaust and their offspring.

Now that they themselves are older, the adult children of Holocaust survivors can be assessed to find out whether the trauma of their parents lingers on to affect their aging process. The results provide important data not just about Holocaust survivors and their offspring, but also in general about aging individuals who were exposed to great trauma.

PTSD is a psychological disorder that develops in some people who have experienced a shocking, frightening or dangerous event. Nearly everyone will experience a range of reactions after undergoing a psychologically traumatic event, yet most people recover from initial symptoms naturally. Those who continue to experience problems may be diagnosed with PTSD. People who have PTSD may feel stressed or frightened even when they are not in danger.

Symptoms must be severe enough to interfere with relationships or work to be considered PTSD. The course of the illness varies. Some people recover within six months, while others have symptoms that last much longer, even for one’s whole life.

PTSD’s symptoms include flashbacks (reliving the trauma over and over, including physical symptoms like a racing heart or sweating); bad dreams; frightening thoughts (including remembering words, objects or situations that remind them of the traumatic event); avoidance symptoms such as staying away from places, events or objects that are reminders of the traumatic experience; and avoiding thoughts or feelings related to the traumatic event.

Fortunately, most children of Holocaust survivors developed into fully functioning and healthy people, but specific groups at higher risk of developing mental and physical morbidity must be pinpointed to offer them suitable interventions that will lessen their suffering.

Prof. Amit Shrira, of Bar-Ilan University’s interdisciplinary department of social sciences and colleagues studied more than 187 matched pairs of parents – including some who survived the Holocaust and some who weren’t exposed to the Holocaust – and their adult offspring (374 individuals in total). The results were recently published in the journal Psychiatry Research.

The authors noted that offspring tend learn from the health behaviors of their parents, both positive and negative. For example, when parents drink alcohol excessively or smoke tobacco, the children tend to adopt these bad behaviors as well. If parents exercise and eat nutritious food, children also tend to emulate them. The correlation between parents’ health behaviors and their children’s behaviors can go on for decades into adulthood.

Holocaust survivors may have adopted unhealthy behaviors so as to decrease distress related to PTSD symptoms and other negative emotions, the authors noted. For example, substance abuse can serve as self-medication against hypervigilance, sleep disturbances, nightmares, unease and guilt. They may avoid exercise because bodily arousal during physical activity can remind the survivors of their body’s response during traumatic events.

Survivors who engaged in behaviors harmful to their health may have been more lenient about their children’s risky behaviors or may even have encouraged such behaviors when their offspring were growing up. It may also be that having pressures, agitation and conflict when they were raised had a negative influence on the children. Indeed, previous studies have shown that children exposed to such an environment at home developed substance use disorder decades later.

Shrira found that Holocaust survivors with signs of PTSD and their offspring reported more unhealthy behavior, such as smoking, alcohol consumption and lack of physical activity, compared to those with no signs of PTSD or no exposure to the Holocaust and their offspring. In addition, Holocaust survivors with signs of PTSD and their offspring reported more medical conditions and disability, which suggests a less successful aging process.

“There is much evidence that traumatic exposure can mold the way survivors’ age. Holocaust survivors who suffer from PTSD tend to engage in unhealthy behavior and transmit this behavior to their offspring, which influences their health and functioning in later years,” said Shrira.

The cause of the intergenerational transmission of trauma is still unclear, but Shrira suggested that there is initial evidence of biological mechanisms involved in the process.

The current findings suggest that unhealthful behaviors should be assessed among offspring of Holocaust survivors, especially among those whose parents suffer from PTSD. This carries important clinical implications, the Bar-Ilan researcher concluded. Screening of offspring patients should cover smoking, alcohol consumption, the use of harmful drugs, exercise and eating habits. In cases where unhealthy behaviors are identified, family physicians should provide information about related health risks and initiate treatment to stop their negative health behaviors.

Source: Israel in the News