The Women who Saved the Dagan Hill

Today, the Dagan hill in Efrat is a bustling neighborhood of close to 400 Jewish families, with a high percentage of immigrants from the United States. But Dagan, on the northernmost edge of Efrat, would likely be a suburb of Arab controlled Bethlehem if not for the heroic efforts of an extraordinary group of women in July of 1995. Marilyn Adler, Sharon Katz, Eve Harow and Nadia Matar share their story.

Tell me about your backgrounds and how you came to Efrat.

Marilyn: I was born and raised in Brooklyn, the daughter of Holocaust survivors. I came to Israel to study the Bible at a seminary, and then returned a few years later, and immediately joined a settlement in the Sinai Desert to protest Israel’s evacuation [as part of Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt]. My husband and I came to Efrat in 1989, which at that time was a small community of 300 families where we felt we could make a difference.

Eve: We made Aliyah [and moved to Israel] from Los Angeles in 1988 and moved straight to Efrat. The First Intifada, a terror war against Israel, was in full swing, and we made Aliyah right into it. We were the 300th family, and I was pregnant with our fourth child. We felt we could fit in here.

I was involved in one pro-Israel demonstration in Beverly Hills before we made Aliyah, but otherwise I wasn’t an activist. Making Aliyah changed my personality. When you make Aliyah – not because of persecution, but because you want to be here – there is a drive inside of you to make a difference.

Sharon: We made Aliyah with five kids from Woodmere, NY in 1992. In America, I was the Eastern Editor of the Hollywood Reporter, writing about the entertainment industry. In Israel, I would use my writing skills in ways I never dreamed of – to fight for Israel.

Nadia: I grew up in Belgium, made Aliyah in 1987, and met my husband, an American oleh, after I came here, and moved to Efrat soon afterwards, to help settle Judea and Samaria. We felt that making Aliyah was not enough, that we had to continue making Aliyah every day, to do more for the people of Israel.

After the First Intifada (an Arab uprising against Israel), when things settled down, we would drive to Jerusalem through Bethlehem – it was the only road at that time – and would see only one soldier along the way. Life was relatively calm, and my plan was to be a stay-at-home mom. Things turned out differently!

For many of our readers, the Oslo Accords are like a bad dream; you want to wake up and forget it ever happened. But as Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” What was life like on the ground in Efrat in 1995? What was the government planning to do with the Dagan hill?

Nadia: In 1992, Rabin and Peres came to power, after making their four famous promises – no talks with the PLO, no division of Jerusalem, no Palestinian state, and no abandoning the Golan Heights. But very quickly, they showed their true intentions, and soon began negotiations to give away the Golan. The Oslo Accords followed soon afterwards.

Eve: I remember the day Oslo was signed. We were watching it on the news, and I started sobbing. Here we were, giving away places that are part of who we are – to an enemy. It was clear that we wouldn’t be able to go to Joseph’s Tomb, that Hebron was a mess. We felt the government had betrayed us. They pushed Oslo through very undemocratically, stealing votes.

Sharon: On the day the Oslo Accords were signed, my children and I were driving home through Bethlehem from Jerusalem. Suddenly a mass of Arabs ran into the middle of the street and began dancing around our car – dancing, chanting and laughing. We all said the Shema prayer, and thank God came home safely, but I never forgot that chilling moment.

Nadia: Seeing the way things were going, my mother-in-law, Ruth Matar, insisted that we had to do something. So we created a movement to show the world that the land of Israel belongs to the Jewish people. We called it Women for Israel’s Tomorrow, because there is no tomorrow without Judea and Samaria. It was a way to demonstrate that not only settlers with long beards cared about the Land, but also “normal” wives and mothers. Ultimately, the media began calling us Women in Green, because at one of the protests we were wearing green hats.

The first Oslo agreement was signed in 1993, the Arabs began their terrorist attacks in 1994, and the second Oslo agreements were signed in 1995. According to these agreements, any open area in Judea and Samaria, even if it was designated to be part of a Jewish community, would be handed over to the Palestinian Authority. At that time, the Zayit, Tamar and Dagan hills of Efrat were not yet built, and we realized they would be given away. That’s what pushed us to act.

Marilyn: Day-to-day life in Efrat was normal, and the town was thriving. But the Oslo Accords loomed over everything. The government was putting us at risk by creating indefensible borders and arming the Palestinians with 40,000 guns. We spent many evenings going to demonstrations with our children.

Eve: It was clear that the Palestinian Authority was not our friend, even though the Rabin government had just given them guns, foolishly thinking the PA would help fight Islamic Jihad and Hamas, who still hadn’t seen the light about the benefits of peace. Anybody who was against this, of course, was labeled as “anti-peace”. The media was constantly smearing the settlers and the settlements.

Tell me about the planning of the Dagan hill demonstration. How did the four of you pull it off?

Marilyn: The neighboring hill of Tamar was slated for construction; it was meant to become a new neighborhood of Efrat. But Arabs began protesting there, and the government acquiesced and stopped the construction. We knew we had to do something in response. We couldn’t stay passive! We were inspired by the women of Hebron, women like Miriam Levinger zt”l, who moved into Beit Hadassah in 1979 and successfully established a Jewish presence there.

Nadia: The four of us began meeting in Efrat to figure out what to do. We chose to make a statement on Dagan, which was the furthest undeveloped hill designated for Efrat that we could reach. These hills belonged to us, even if they weren’t developed yet.

Sharon: We hoped that if we could hold onto Dagan, the northernmost hill in Efrat, and create a Jewish presence there, the hill and everything to its south would be included as Jewish land in the peace talks. So we organized a group of friends, most of whom were Anglo, and we called them individually and asked them to join us in a Zionist act. This was long before WhatsApp!

Marilyn: We didn’t tell the other women the specific details of our plan. It may sound crazy to you, but since we were activists, we were afraid our phones were tapped. All we told the other women was that we were planning something “for the sake of the Land of Israel”. And they all answered “Hineni,” “We are here and ready”.

Nadia: We told the women – “be ready on July 20, make sure your husbands are available to watch your kids, and bring a sleeping bag and a flashlight”. Only when the day came did we tell everyone, “we’re going to the Dagan!”

Walk us through your “Aliyah” to the Dagan hill. Did anyone try to stop you?

Eve: The day finally came, and we drove up to the Dagan towards the end of the afternoon. It wasn’t prohibited to go up to the Dagan at that time; it only became a closed military zone after we went up there. But it was hard to get to; there was only a dirt road to the Dagan, so it was a bumpy ride. We wrecked our tires that week.

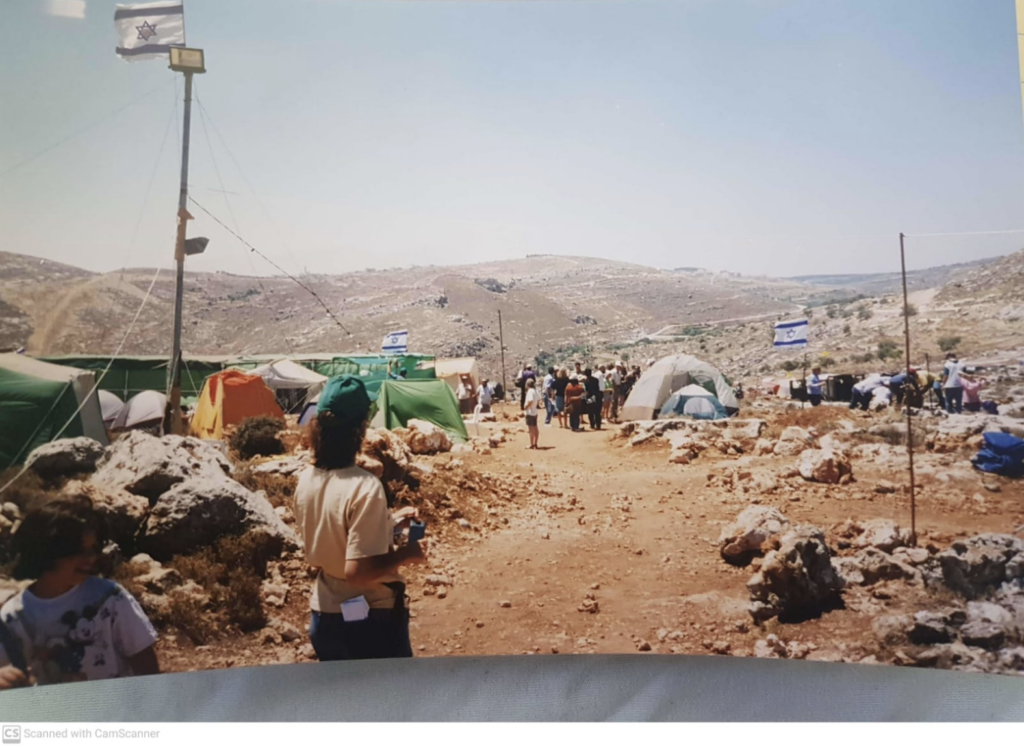

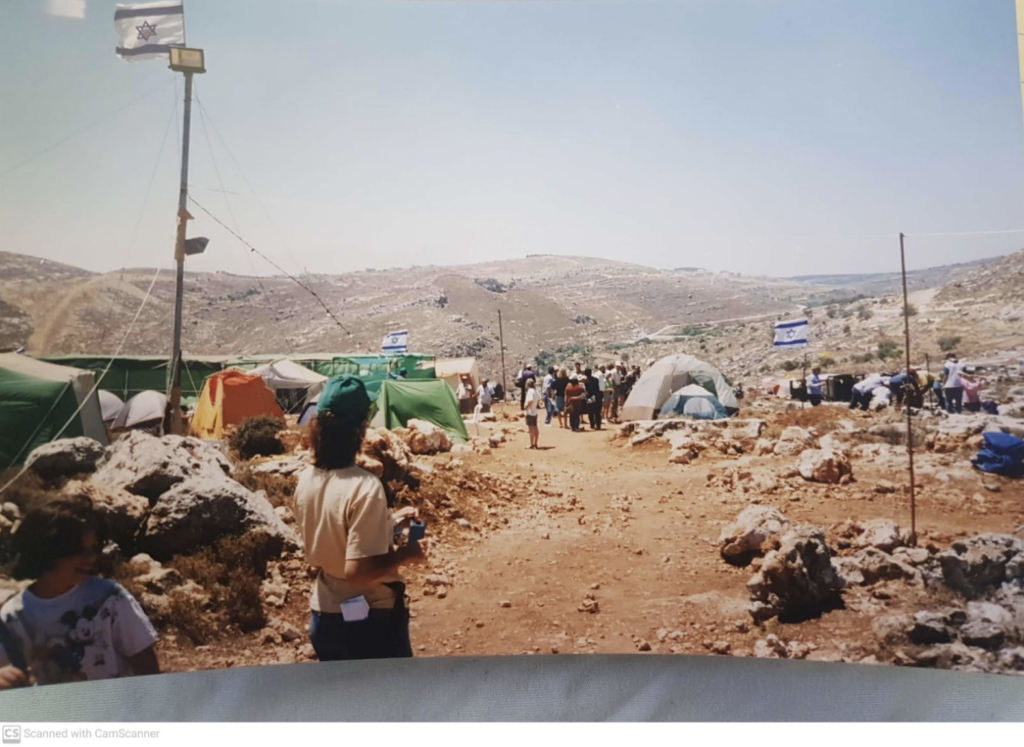

Sharon: We immediately planted Israeli flags and our signs, “Dagan Hill” and “Jewish Mothers for the Land”, and started setting up camp. Shortly afterwards, the army came and asked us what we were doing. We told them clearly why we came: “We are holding onto the Land of Israel!” They seemed amused, and said: “Have a nice picnic. Leave before dark and don’t plant any trees!” and then left. We were surprised; we thought we would be quickly arrested or evicted. But they didn’t take us seriously. The moment they left, we pulled baby trees out of our trunk and planted them!

Eve: We did not think we would be up there for almost two weeks; we thought we would stay the night, have a demonstration and get some press. Each morning we woke up and wondered how we were still there. At the time, civil disobedience and massive demonstrations hadn’t yet taken off.

Marilyn: When night came, it was frighteningly dark. My husband Josh, Sammy Fenner and Dr. Baruch Sterman, who had helped with the planning, came to do guard duty. Though many of the women carried pistols, we felt we needed more protection.

Eve: Nobody was fooling themselves that we were camping out at a park; Dagan is right next to southern Bethlehem.

Marilyn: We prepared press releases in advance to be given to the news agencies, flyers for Efrat, as well as a car with a megaphone to announce in Efrat: “we have liberated the Dagan – come join us!”

Throughout that first night, people from all over the Gush joined us on the hill. There was no electricity, so Ilan Paz from Alon Shvut brought a gigantic floodlight and other equipment. I remember Nadia got a call on her satellite phone. She answered: “Shalom, you’ve reached the Dagan Hill!”

Nadia: We began calling people to tell them we were on the Dagan, and little by little word spread. More and more people came – there was electricity in the air. It was a moment of elevation of the spirit.

Eve: We had this overwhelming feeling that maybe we’re making a difference, that we could actually do something to save a part of the land of Israel.

Marilyn: Early the next morning, we saw a group of Efrat women walking up the long path with coffee and cake – a godsend! Dozens of people started showing up with tents, and soon Dagan became a tent city. As more and more people came, it was my job to coordinate who slept in each tent. I offered Rabbi Shlomo Riskin a quiet spot on the edge of the camp, but he wanted to stay in the middle of the camp. Wearing a suit and tie, he opened up his Gemara and sat and learned!

It was Friday, and over a hundred people worked to prepare the camp for Shabbat. We set up a huge tent as a dining room, and another as a synagogue. People brought a Torah scroll and food and drinks for everyone who would stay on the hill for Shabbat.

We had a beautiful Shabbat. In the late afternoon, we saw a huge group of people from Efrat coming to join us for the traditional meal eaten at the end of Shabbat. It’s a moment I’ll never forget.

You ended up staying on the Dagan hill for twelve days. What did you do while you were up there?

Sharon: I helped organize the food for a camp full of “residents”, visitors and volunteers. We built a make-shift kitchen that was always stocked. Other women organized activities for the kids, Bible classes and prayer. It really became a new community with an incredible devotion-to-Israel vibe.

Politicians came up all the time and asked us what we wanted. Our response was always the same: “We want to hold on to our Land”. “Do you want a cemetery? Or a forest? Then you can put up a caretaker house.” “NO! We want the Dagan to be part of Efrat, a community with homes and children.” I think they were exasperated that we wouldn’t compromise. But we weren’t politicians. We were women who loved the Land.

Nadia: As our stay on the Dagan lengthened, each woman made arrangements for their families. Many of the kids joined us on the hill. It wasn’t simple, juggling our families, the demonstration and the press. Our husbands made it possible.

Eve: My four-month-old baby was with me most of the time, because I was nursing him. And my husband and five other kids would come in and out all through the time we were there.

During the protest, we uncovered man-made shafts in the ground. We called in archeologists to investigate it, and it turns out these shafts were part of an ancient aqueduct system built during the second Temple era, to bring water to Jerusalem – an incredible feat of engineering. The discovery gave us strength; it drove home that these hills belong to us, to our people.

How did the media react to what you were doing?

Eve: We were amazed by how much attention we received from the press – we were front page news. The local radio stations started each morning by broadcasting “Good morning to the women of the Dagan Hill!”, and every night, the evening news opened with an update on what was happening on the Dagan hill. We couldn’t believe it.

We hosted a major press conference on the Dagan hill, and arranged for a tractor to be there to start digging for the future neighborhood’s cornerstone while the press were there.

Members of Knesset, like Uri Ariel, came to sit with us, and they asked us what we wanted. We made clear that this demonstration was not just about Efrat – it was about all of Judea and Samaria. At every press conference, we encouraged other communities to do what we were doing.

Nadia: We were the match that lit a much greater fire. Other communities, like Beit El and other places, soon followed our example.

Marilyn: We had great success with both the right- and left-wing press. They saw us as “pure”, without any ulterior motives. They saw that we were very dedicated to the Land of Israel and that we were justified in our fears of what the Oslo Accords would bring. But we were also “normal” people who didn’t fit the “settler” mold.

Sharon: We were mothers, and we were new immigrants. They couldn’t believe how normal we were! I remember one of the journalists writing “their accents were music to my ears”.

Eve: Ron Maiberg, a culture reporter from Ma’ariv, came to speak with us. He was very surprised by what he saw. These were not the settlers he was expecting. A lot of the women were wearing jeans, and some had advanced degrees. We were weird ducks. These were not typical “settler women,” but rather American women who lived in nice houses and who were trying to make a point. His article was very important for framing this as an unusual demonstration, as something different.

Nadia: The journalists admired us. We were there in the middle of the summer, it was incredibly hot and there was no air conditioning.

Eve: Many people were involved in what happened on Dagan, people who didn’t receive attention or recognition. There is no way the four of us could have done this on our own. But the press were interested in this angle – that four mothers who didn’t seem like classic “settlers” were leading this demonstration. So we went with it. It put a positive spin on the whole story, making it less militaristic, and helped Israeli society see us differently.

The Dagan demonstration also changed the way our Israeli neighbors viewed us. Steve Rodan from the Jerusalem Post wrote about the powerful impression we made on the Israeli women in Efrat, some of whom originally viewed us as spoiled Americans.

Coming from America, where we had to build Jewish community for ourselves, perhaps we had more of an activist mentality than many of the Israelis, who were used to the government building schools and synagogues for you.

[Ed. note: On August 4, 1995, Rodan wrote: “For the Israeli-born women in Efrat, the sight of women leading men… appeared novel. They acknowledge that most Israeli women would not dare to confront both the government and the norms of their male-centered society.”]

Nadia: I remember a journalist said to me: “you know you’re going to be evacuated soon, right?” I said: “So what, we’ll come back up! We’re going to build a neighborhood here for our children – and one day, we’ll invite you for coffee.” She said: “time will tell”. I think it’s time to invite her back to Dagan!

How did the demonstration on Dagan end?

Marilyn: The police came every day we were there, saying this was an illegal outpost and they had orders to take us off the hill. One morning, we even woke up to eviction notices taped onto our makeshift kitchen. But they never did anything.

I had a good relationship with them and I believe they respected what we were doing. I asked a policeman to let me know when the eviction would be, because there were many young children on the hill and I wanted to avoid a traumatic situation. The police officer told me when the eviction would happen – on July 31 – and we quickly got the word out to people all over the country. On the day of the eviction, over 1,000 Jews came from all over Israel to support us.

We studied Martin Luther King’s example of civil disobedience, to ensure there would be no violence. We would be like a sack of potatoes – we wouldn’t fight the soldiers, G-d forbid, but we would make them carry us. We printed out flyers with guidelines, to ensure nobody spoke negatively or acted violently. On the day of the evacuation, we yelled into the megaphone: “Brothers, brothers, we love you – we’re doing this for you and all of the Jewish people!”

Eve: On the last day, when the army came to physically remove us from Dagan, it took them all day. We sat in a circle with our arms locked together, and chained ourselves to one another.

When they brought us down to the bottom of the hill, we would run back up. It was a chaotic scene. The government didn’t really know how to handle us; they hadn’t experienced this before. This was before the forced evacuation of Gush Katif in [the Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip].

Sharon: As we were being dragged off the hill, we shouted over and over again: “It doesn’t matter how many times you remove us, we’ll be back again and again, because this is our home and our Land!”

Marilyn: Over 200 of us were arrested, put on buses, and brought to the Russian Police Compound in Bethlehem, where the Israeli army had a base. Some of us were released later that day, while others were kept overnight.

Eve: People had a hard time absorbing that someone like me, an American immigrant, could end up nursing her baby in a jail in Bethlehem after getting dragged off a hill.

Nadia: As soon as we got home, we began planning our next protest at the Dagan. Hundreds of us went back up to Dagan the next night. This time, we were quickly arrested and brought back to Bethlehem.

Unlike the first time, however, they then put me and Rabbi Shlomo Riskin in a van. We drove for hours, and had no idea where we were going. We only found out afterwards that activists all over Israel had heard we were arrested and were demonstrating on our behalf, demanding that we be released. To avoid the demonstrations, the army drove us on a roundabout route to the Abu Kabir prison in Tel Aviv. All night long, I heard hundreds of demonstrators protesting outside of the jail. The next day, I was brought before a judge, who released me on bail. Months later, we had a court case, and I was punished with two hundred hours of community service.

In the meantime, as soon as we were released, we planned our next Aliyah to the Dagan. That time, we brought large shipping containers to the hill, to make it more difficult for the army to take us down.

Ultimately, you won the battle for Dagan. What changed the government’s mind?

Sharon: One of the reasons we succeeded was that we didn’t know we couldn’t. We didn’t know that we couldn’t stand up against the government, we didn’t know women couldn’t fight for the Land, we didn’t know that mothers had no chance against the army. We didn’t know we couldn’t fight in our own way for the Land of Israel, so we succeeded.

One morning we woke up to an Arab protest right outside our camp. The Arabs had a big sign that said “fair well”, instead of farewell. We took that as a good sign. They were wishing us good luck!

Nadia: The local council in Efrat eventually got involved and took over the battle for Dagan and the other hills that were not yet built. In the end, the local council reached an agreement with the government, and a religious school was established on Dagan, Yeshivat Siach Yitzchak. When this agreement was reached, we declared victory, and we moved on to fighting Oslo in other areas of the country, and then Gush Katif.

Marilyn: There is a backstory to the victory that we only found out about later. At some point after the Dagan demonstrations, the Israeli government met with the Palestinian Authority to decide which lands would be part of Areas A, B and C in Judea and Samaria. A military officer who was at the meeting told us that they initially planned to include the Dagan and Tamar hills in Area B, under Arab control. But then they changed their minds. They said: “Put those hills in Area C, we don’t want to deal with those crazy American women again!”

Looking back 28 years later, what did you learn from the experience? How did it change you? And what lessons would you share with the next generation of immigrants to Israel?

Nadia: When there is a decree, you can’t stay home and kvetch, you have to get up and act! This is what I learned from the Levingers and the Porats, [the leaders of the settlement movement] and from our experience on Dagan. We realized that if the government was afraid to act, we would have to step in and ensure the Land would remain ours. Sometimes history calls upon us to leave our comfort zones and act. Thank God, we succeeded. Today, after the forced evacuation of Gush Katif, I understand that settlement is not enough. The only way we will safeguard our being here is by applying Israeli sovereignty over Judea, Samariaand the Jordan Valley. That is what Yehudit Katsover and I dedicate all our time to with the Sovereignty Movement.

Sharon: Act like an immigrant. No matter how many years you are in Israel, live here as if you are new. Then every stone becomes precious to you. Act like an immigrant – be naïve. Don’t accept the fact that you are only one person and cannot possibly make a difference. You can! If you give your heart to the Jewish people, you can and will succeed.

Eve: I didn’t fight in any wars or do national service. Here was a chance for us to do our part to hold onto the land of Israel, to be a part of this great story. I don’t think people expected it from women in a place like Efrat, which has a bourgeois image. But people here did some amazing things, things that were not easy to do.

For me, the Dagan was the beginning of an entirely new chapter in my life. Oslo was a wake up call that we couldn’t assume Judea and Samaria would be ours forever. We have to fight for it. Not enough people have yet woken up, and so we still have to fight.

I ended up with a radio show on Arutz Sheva which turned into a podcast, Rejuvenation, on the Land of Israel network, which I still have until today. I began speaking about Israel, doing advocacy work, and eventually became a tour guide and got another masters degree, to teach people to appreciate our Land. I couldn’t dedicate my entire life to protests and demonstrations; I needed to focus on the sunny side of Israel too.

Today I was giving a tour in Samaria, where “little” people are doing unbelievable things, acts of incredible sacrifice that will never make the headlines. These are the truly great people, who prove that we can all make a difference. Not doing anything is tantamount to letting the bad guys run the show.

Nadia: When I grew up in Belgium, we did not experience antisemitism. We had a good Jewish life, and I went to Bnei Akiva. But I always felt like a stranger – that I wasn’t home. When I came to Israel for the first time, I realized that this is where I belong. Of course, a Jew should be allowed to live wherever he wants to. As individual Jews, it’s possible to live a very nice life in exile. But as a people, there is no future for us anywhere but Israel.

If you want to make Jewish history – you can only do that in Israel. As Jews, we can choose to be players on the soccer field, or spectators who watch the game from the stands. Come and be part of those who are playing on the field; don’t just be a spectator! If another million Jews come home, the world will see that this Land is ours.

What did the Dagan experience mean for your family?

Marilyn: My children had a firsthand and powerful Zionist experience right here in their own backyard, which strengthened their convictions regarding our rights as Jews in all parts of Israel. Not surprisingly, some of our children have made their homes on the Dagan. We have four generations of my family living here. I have to pinch myself to believe it!

Sharon: This summer, my family celebrated our 30th anniversary of moving to Israel. We took a tour of Efrat from the south to the north, the Rimon to the Dagan, and we told the story of our family on each hill. Love of our community and our willingness to struggle to keep it and build it, is in the blood of our children and grandchildren. Today my eldest son lives in the Dagan; he met his wife during the Dagan demonstration when they were teenagers!

Eve: I get a lot of joy going to visit my son, who also lives in the Dagan with his wife and three kids, because I remember looking out of the bus as they were taking me away to jail and seeing my son standing with my husband, watching me get arrested.

It wasn’t easy for the kids. We were trying to be an example for them, to show them what love of the country meant, and that you have to sacrifice. Many people made far bigger sacrifices down the road.

Sharon: I remember standing on Dagan in 1995. We had an incredible view of the “old Efrat”, and dreamed that one day, Dagan would be connected to Rimon, Efrat’s first neighborhood, like a string of pearls. We dreamed it – and it came true.

The post <strong>The Women who Saved the Dagan Hill</strong> appeared first on Israel365 News.

Israel in the News