Cremated Remains Found in Israeli Archaeological Site Signify a 7th-Millennium Cultural Shift in Funeral Practices

Burying the dead was the conventional way of disposing of the bodies of the departed in ancient times. Now, archaeologists and anthropologists have uncovered the oldest-known case of intentional cremation of human bodies in the Near East – dating back 9,000 years to the Neolithic Period.

Excavations at the Neolithic site of Beisamoun in the Hula Valley in northern Israel have uncovered an ancient cremation pit containing the remains of a corpse that appears to have been intentionally incinerated as part of a funerary practice.

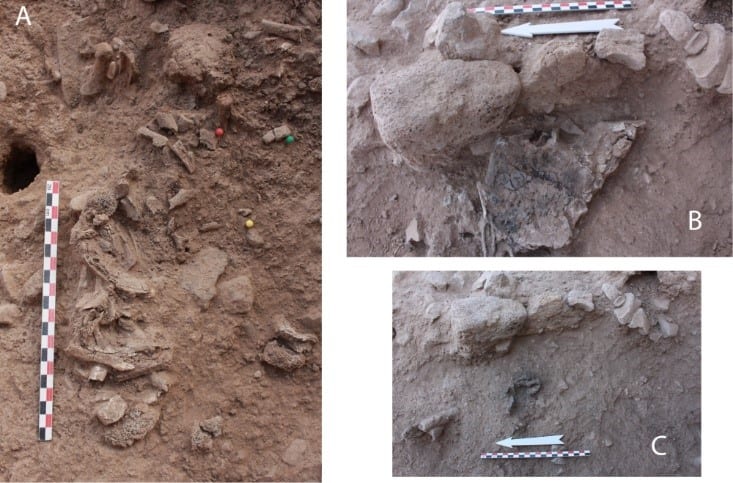

Picture of bones in situ: A. Segment of axial skeleton: ribs and vertebrae exposed in the middle of the structure. B. Right coxal in situ; preserved almost complete by a piece of collapsed mud wall (see Fig 2D). C. Four right pedal proximal phalanges found directly under the right coxal.

(Photo credit Bocquentin et al, 2020)

The findings have just been published in the open-access journal PLoS (Public Library of Science) from a team led by Dr. Fanny Bocquentin, a leading bioanthropologist at the the French National Center for Scientific Research and colleagues at the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Zinman Institute of Archaeology at the University of Haifa, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s National Natural History Collections and others in the US, Canada and France.

The remains comprise most of one skeleton of a young adult whose bones show evidence of having been heated to temperatures of over 500°C shortly after death. They were found inside a pit that appears to have been constructed with an open top and strong insulating walls. Microscopic plant remains found inside the pyre-pit are likely leftover from the fuel for the fire. This evidence led the authors to identify this as an intentional cremation of a fresh corpse, as opposed to the burning of dry remains or a tragic fire accident.

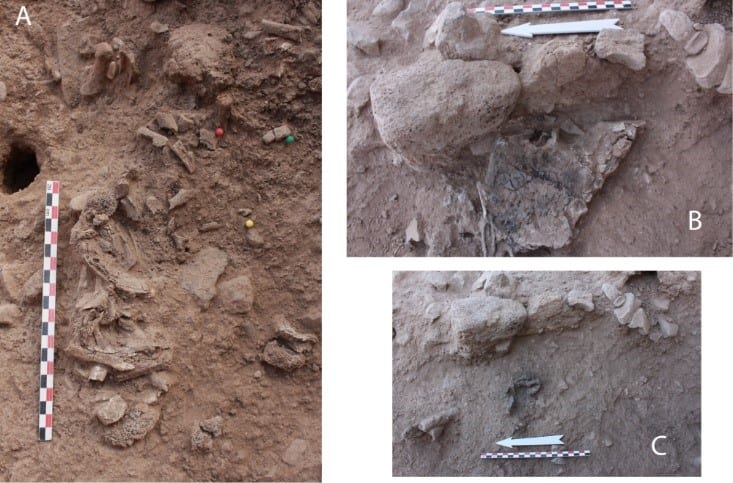

Beisamoun pyre fields (Photo courtesy Beisamoun project)

These remains were directly dated to between 7013 to 6700 BCE, making them the oldest known example of cremation in the Near East.

In the autumn of 2007, a major salvage excavation took place on the western margins of Beisamoun in the Hula Valley as part of the development of the Rosh Pina-Kiryat Shmona highway. Excavation in the western part of the greater area of the Beisamoun site, formerly known for its Pre-Pottery Neolithic finds, revealed a wealth of a archaeological objects attributed to an early phase of the Pottery Neolithic period.

This early cremation comes at an important period of transition in funerary practices in this region of the world, the researchers noted. “Old traditions such as the removal of the cranium of the dead and the burial of the dead within the settlement, were on the way out, while practices like cremation were new. This change in funeral procedure might also signify a transition in rituals surrounding death and the significance of the deceased within society. Further examination of other possible cremation sites in the region will help elucidate this important cultural shift.”

Bocquentin wrote in the 44-page article that the funerary treatment involved on site cremation within a pyre-pit of a young adult individual who previously survived from a flint projectile injury. The inventory of bones and their relative position strongly supports the deposit of an articulated corpse and not dislocated bones.” She added that “this is a redefinition of the place of the dead in the village and in society.”

The researchers used a multidisciplinary approach that integrated archaeothanatology, spatial analysis, bioanthropology, zooarchaeology, soil micromorphological analysis to reconstruct the different stages and techniques involved in this ritual. The origins and development of cremation practices in the region are explored as well as their significance in terms of Northern-Southern Levantine connections during the transition between the 8th and 7th millennia BCE, she continued.

“The treatment of the dead during the Neolithization process in the Near East was a complex process, embedded in a cognitive and symbolic world that underpinned the economic and dietary shift from hunting and gathering to agro-pastoralism,” wrote the researchers.

“Burial location and funerary gestures varied from one community to another as well as between one individual and another within the same site. Thus, several operational sequences in burial practice coexisted resulting in primary, secondary, plural, single, staging, manipulations and/or skeletal element removal that were carried out, sometimes side by side. Occasional defleshing and/or dismemberment, and temporary mummification are also suspected to have been practiced.”

The bones were distributed throughout the bottom of the pit, partly superimposed one on the other to a thickness of 40 centimeters. “However, the density of remains was not very marked except at the center of the pit. If there was an apparent anatomical disorder at first glance, by looking at the details some interesting patterning could be observed. Cranial and mandibular fragments were found only in the southern half of the structure,” the authors continued.

“Next to the south wall on the upper level, we found the base of the skull; the rest of the cranial vault and face were found slightly lower down at the center of the pit. Conversely, the cervical vertebrae were dispersed out from the center to the northern half of the pit. The thoracic column and some of the ribs were concentrated in the center, roughly following a west-east direction. The lumbar vertebrae were found in the middle and against the southwestern wall.”

Israel in the News