The Hebrew University of Jerusalem has just celebrated the Albert Einstein’s 140th with a cake, a visit from Texas of his cousin – and the presentation of 110 original manuscripts to its Einstein Archives.

The university, of which the illustrious theoretical physicist was a founder a century ago, is – according to his will – the beneficiary of all of Einstein’s intellectual property. The latest addition to the archives was donated to the university by the Crown-Goodman Family Foundation of Chicago after purchasing it at an undisclosed sum from Dr. Gary Berger, a preventive medicine physician in Chapel Hill, North Carolina who had obtained it from antiques dealers.

“Einstein’s writings are part of our legacy,” said HU president Prof. Asher Cohen who opened a press conference on Wednesday at the university’s Givat Ram campus. “We have his most important documents, including his handwritten Theory of General Relativity and subsequent ones. Einstein also helped raise funds for HU. He and [Israel’s first president Dr. Chaim Weizmann sailed from Europe to the US to raise money for the university. Weizmann was asked if after being with the genius physicist for two weeks if he understood Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. He said: ‘I am now fully convinced that Einstein understands it.’ We know expand this eternal home of the Einstein legacy,” Cohen concluded.

Dr. Roni Gross said that after Einstein’s death in 1955, his longtime secretary Helen Dukas fulfilled his request and made order out of his “heap of papers” for sending to HU. It now contains more than 82,000 documents, mostly written by hand in German, with a minority in English when he worked at Princeton University in New Jersey.

“Today, all manuscript collections have been digitized, so the public expect to get all documents immediately as digital images, for free and by clicking their computer mouse. However, it’s still very important for archives to have the original material, because it provides a special magic, and without the originals, the collection have a lower status.”

Prof. Hanoch Gutfreund, a former HU president who is a prominent theoretical physicist and Einstein expert, told assembled journalists: “We invited you to Einstein’s birthday party. And for that, one needs a gift. These manuscripts are a gift to us and to Albert. All these unique writings have come to the place where he wanted them to be.”

One of the documents was a postcard written in German to Michele Besso, a Jewish friend of his, in 1916. “Albert had finished his Theory of General Relativity. He told his friend that he had a ‘brilliant idea.’ Today it is basis of modern laser technology,” said Gotfreund.

In a letter to Besso written in 1951, Einstein said that in 1905, he had discovered that light under certain circumstances is made from light particles. But he confessed that after half a century, he still didn’t understand it. He also discussed with his friend personal issues, such as about his estranged wife and their families and about Jewish identity.”

“They had exchanged dozens of postcards and letters from 1903 until Einstein’s death in 1955. Some remained with Besso’s family. Each is a gem.” Another unique item was a letter Einstein wrote from the US in January 1935 to his elder son Hans Albert in Switzerland. Having divorced his first wife Mileva, Einstein spoke about the health of his younger Edward, who suffered from mental illness, for which his mother sent his to a psychotherapist, apparently Sigmund Freud.”

Gutfreund noted that Einstein was apparently naïve in thinking not long before the beginning of World War II that war with Germany would not break out.

“From his handwritten manuscripts, you can see what Einstein crossed out and when he changed things. We have items that were not published but would become part of a future paper. He wrote a little note on the basic principle underlying the physics of the atomic bomb and nuclear reactors. In 1946, after the atom bomb was dropped on Japan, Einstein described in Science Illustrated a similar principle. He was worried about the effects of the bomb on humanity,” said Gutfreund.

“Many of the papers arrived loose and not in order. They still require original research. Today, we apply technology to get answers, such as analyzing the ink and the paper quality.”

A surprise guest at the press conference was Karen Cortell Reisman, who was born the same year that Einstein died 64 years ago. Today a professional training and speech coach and author in Dallas/Fort Worth, she has known since she was a child that her grandfather was a cousin of Einstein.

Her mother and father were married only a week before July 4, 1949, soon after they had immigrated from Europe to the U.S. They spent the day visiting cousin Albert in his Princeton office. Her mother was nervous about meeting him, as she was the outgoing type and her husband was a quiet, intellectual type who warned her not to scare the scientist by being too overwhelming, Reisman related.

“After she sat silently for several minutes, Einstein – in his baggy gray sweater and old trousers – stood up and put his arm on my mother’s shoulder. He said: ‘I am a normal human being like everyone else.’ And it calmed her down. They had a wonderful day together – three new immigrants from Europe after the war.”

Reisman herself obviously had never met Einstein, but as her parents hanged Einstein’s letters (albeit in cheap frames) on the wall, she was always aware of the connection. “I inherited from him my frizzy hair,” she joked.

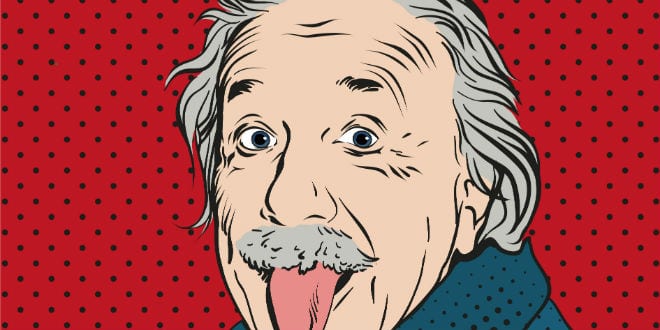

Reismann presented to Gutfreund her own gift, a copy of the original photo of Einstein when he was in a car and tired of journalists following him – and sent copies of it to his relatives. He stuck his tongue out of them in the very famous photo. “I don’t mean this about you,” he told his cousins.

Source: Israel in the News