“All vows, obligations, oaths, and anathemas, whether called ‘ḳonam,’ ‘ḳonas,’ or by any other name, which we may vow, or swear, or pledge, or whereby we may be bound, from this Day of Atonement until the next (whose happy coming we await), we do repent. May they be deemed absolved, forgiven, annulled, and void, and made of no effect; they shall not bind us nor have power over us. The vows shall not be reckoned vows; the obligations shall not be obligatory; nor the oaths be oaths.” -Kol Nidrei Prayer

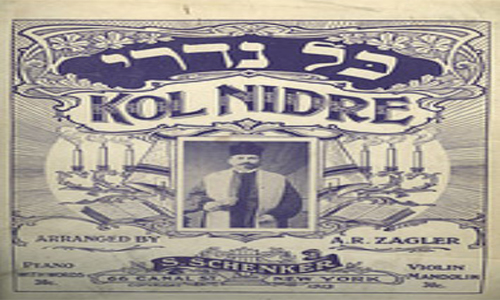

Tonight begins Yom Kippur – the holiest day on the Jewish/biblical calendar. The holiday always begins with Kol Nidrei, one of the most well-known Jewish prayers. Yet, the mysterious question is … why do we begin Yom Kippur with this strange prayer? What seems more bizarre is that it is not even a prayer at all but rather a technical legal formula.

Throughout the centuries, great rabbinic and halachic minds have actually tried to get rid of this prayer. The first mention of it is in an 8th century responsum by Rav Natranai Gaon. Most of the gaonim and rishonim apposed this prayer. Rabbeinu Tam, the grandson of Rashi, thought it was scandalous and should not be recited. Even Samson Raphael Hirsch, the father of Modern Orthodoxy, tried to do away with it in his first congregation in Germany. Yet this prayer has outlived all of its critics. Despite the repeated attempts in every generation to exclude this prayer, it’s still there. And interestingly, instead of the rabbis, it has largely been the common people who have chosen to keep it.

So what is it about this beloved and quintessential Jewish prayer? In my opinion, Kol Nidrei, and the halachic declaration right before it, can serve as an illustration of what Yom Kippur is really about, for within them are hidden lessons of the mysterious nature of this special evening.

First of all, Kol Nidrei teaches us about the tension, mystery and paradox of Yom Kippur. It has already been mentioned that Kol Nidrei is not even a prayer at all. Rather, it is a halachic declaration for the annulment of vows. For example, with all the beautiful parts of a wedding, it’s like singing the Ketubah. And yet, we “pray” it. Furthermore, Kol Nidrei actually begins our holiest day of the year.

On this holiest day when we stand before HaShem, you would think we would literally hear the sound of angels wings, float on clouds, and be engulfed by an incredible aura of God’s manifest presence. Although a degree of that does exist, we rather celebrate our holiest day by praying through long lists of sins, repeating ancient words in a foreign language, and discussing at length the role of the High Priest and sacrifices.

There is a tension that exists between our participation in heavenly worship with the angels on Yom Kippur and the realities of the earthly world we inhabit, with all its limitations. On Yom Kippur when we enter the synagogue and hear the sound of Kol Nidrei, we sense that something is different … something special … something holy.

On this holiest night of the year we stand before HaShem and are confronted by the same tensions within ourselves. Between the part of us that is holy and yearns to be re-united with our Creator, and the other part of us in need of atonement. Within each one of us is a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a tension … a war within ourselves.

A Perceived Paradox

What is even more jarring than Kol Nidrei itself is the halachic formula we recite just before hearing the actual prayer:

With the approval of the Heavenly court and with the approval of the congregation; in the convocation of the Omnipresent One and with the consent of this congregation, we declare it lawful to pray with sinners.

Right away you should be struck by the wording, “we declare it lawful to pray with sinners.” It makes you want to look around the room, hushed, and wondering who this is referring to … when you realize this prayer is about you. That each one of us is a transgressor and sinner in need of atonement.

This tension is summed up nicely in a great teaching by Rabbi Bunim of Peshischa: Every person should carry two slips of paper. In one pocket should be a slip of paper which reads, “I am but dust and ashes,” and in the other pocket, a slip of paper which reads “the world was created for me.”

Throughout most of the year we are, as Paul writes in Romans (8:37), “more than conquerors through Him who loved us” and we “can do all things through Him who strengthens us (Phil. 4:13).” But on Yom Kippur, as the opening phrase of our service reminds us, we are all sinners in need of God’s grace and redemption. On Yom Kippur we are confronted not by our strengths, but our weaknesses. And the plural language of our prayers reminds us that we are all in this together and that we are only as strong as our weakest link. Each one of us is responsible for one another … and the sin of one of us, affects all of us.

It says in the Talmud (b. Shavuot 39a):

כל ישראל ערבים זה בזה … All Israel is responsible for one another.

That is why when we stand and recite the sins in the Al Chet, Ashamnu or Avinu Malkeinu, it does not matter whether you personally committed each sin, because someone in the room did and we are now all responsible. On Yom Kippur we are confronted by the reality that each one of us, as individuals, sin, and are personally accountable. But we are also reminded that there is a corporate accountability as well.

Paul wrote in his letter to his young disciple, Timothy:

So here is a statement you can trust, one that fully deserves to be accepted: the Messiah came into the world to save sinners, and I’m the number one sinner! But this is precisely why I received mercy – so that in me, as the number one sinner, Yeshua the Messiah might demonstrate how very patient he is, as an example to those who would later come to trust in him and thereby have eternal life. So to the King – eternal, imperishable and invisible, the only God there is – let there be honor and glory for ever and ever! Amen. (1 Timothy 1:15-17)

On Yom Kippur, we are reminded of the tensions and competing themes of the day, and the tensions and perceived paradoxes within ourselves. As stated above, on Yom Kippur we are confronted by the reality that each one of us is a “Chief sinner.” Within each one of us there is an inner-struggle and a battle between Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. On Yom Kippur we must ask, which one are you?

On Erev Yom Kippur we recite Kol Nidrei, and the halachic declaration right before it that it is now lawful to pray with sinners. And by doing so we are reminded of what Yom Kippur is really about and the hidden lessons of the mysterious nature of this special day.

G’mar chatimah tovah … May you be sealed for a great new year!

Source: Yinon